Medieval Olive Oil Use in Religious Cooking Practices

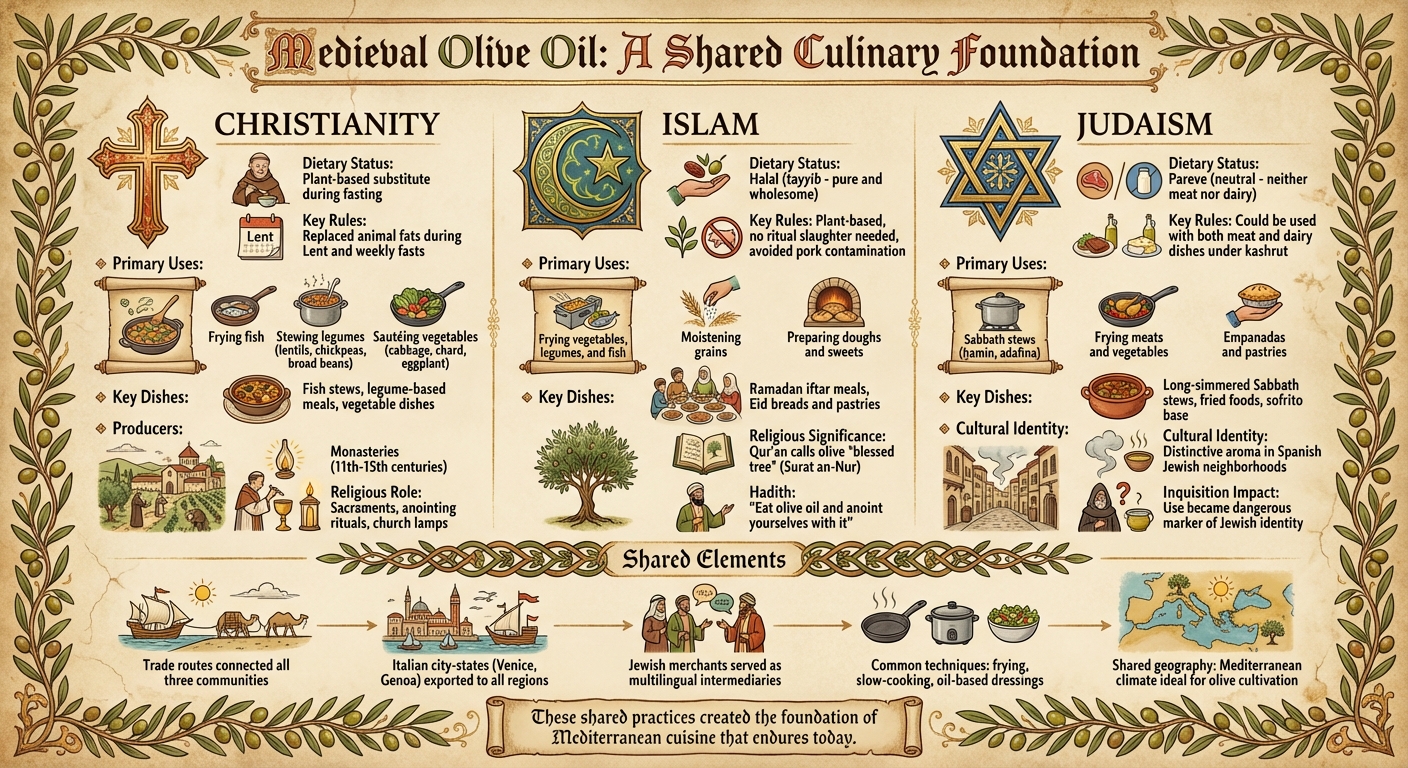

Olive oil was a cornerstone of medieval Mediterranean life, uniting Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities through shared dietary needs and religious rituals. Its plant-based nature made it suitable for fasting rules, halal guidelines, and kosher laws, allowing it to transcend cultural and religious boundaries. Here's a quick overview of its role:

- Christianity: Used during Lent as a substitute for animal fats, in sacraments, and for church lamps.

- Islam: Praised in the Qur'an as "blessed", used for cooking, healing, and religious symbolism.

- Judaism: Classified as pareve (neutral), ideal for both meat and dairy dishes, and central to Sabbath and holiday cooking.

Monasteries and trade routes ensured widespread availability, while olive oil became integral to frying, stewing, and slow-cooking techniques. Its role in shaping Mediterranean cuisine and connecting diverse traditions persists today, with modern producers upholding the same standards of quality and purity.

Medieval Olive Oil Use Across Christianity, Islam, and Judaism

Olive Oil's History in the Medieval Mediterranean

From Ancient to Medieval Times

The story of olive oil in medieval kitchens stretches back thousands of years. In Minoan Crete, around 2000 BCE, large amphorae found at Knossos were used for both cooking and sacred rituals. These traditions were carefully preserved by monasteries, which produced olive oil for daily use as well as for religious ceremonies.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, large-scale agriculture dwindled in parts of Western and Northern Europe, causing a decline in olive oil production in those regions. However, across the Mediterranean, the production of olive oil continued uninterrupted. The spread of Christianity across Europe created a new demand for olive oil, which was used in sacraments, anointing rituals, and church lighting. Monasteries and ecclesiastical estates took on the responsibility of maintaining olive oil operations to meet these needs. Meanwhile, the Islamic expansion of the 7th and 8th centuries brought North Africa, the Levant, and the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule. This expansion not only introduced advanced irrigation techniques but also elevated olive oil's importance due to its religious and cultural significance in Muslim communities.

These ancient practices and innovations laid the foundation for the medieval advancements in olive oil production and trade.

Geography and Production Methods

Medieval olive oil production built on ancient techniques, adapting them to meet both religious and everyday demands. The warm climates of southern Europe, the Levant, and North Africa were ideal for olive cultivation, allowing each region to develop its own refined methods of extraction. Monasteries played a key role in improving traditional practices, such as hand-harvesting and pressing, to increase efficiency and output. Olives were often grown on terraced hillsides and transported to stone crushers, where they were ground into a paste. Lever and screw presses were then used to extract the oil, which was left to settle in large jars so impurities like water and sediment could separate from the oil. Medieval monks ensured that every step - from pruning and harvesting to storage - was done with precision to maintain high-quality production.

Trade Routes Between Religious Communities

Trade routes were essential to the olive oil economy during the medieval period. Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa rose to prominence by exporting olive oil along key maritime routes. These routes connected regions such as Andalusia, Sicily, the Italian peninsula, and the Greek islands to major ports in the Levant and North Africa. Under Islamic rule, trade networks in the western Mediterranean linked Iberian and North African ports, enabling the exchange of olive oil between Muslim territories, Christian Europe, and Jewish communities. Jewish merchants, often fluent in multiple languages and active across various regions, played a crucial role as intermediaries. Thanks to their efforts, a monastery in Italy, a household in Tunis, or a family in medieval Spain could enjoy olive oil produced hundreds of miles away.

These dynamic trade networks helped solidify olive oil's role in religious rituals and culinary traditions across the Mediterranean.

Christian Religious Practices and Olive Oil

Fasting Rules and Diet Changes

Christian fasting traditions elevated olive oil to a central role in the kitchen. During periods like Lent or weekly fasts, Church rules forbade meat and animal-based fats like lard or butter. These restrictions encouraged a focus on penitence and spiritual discipline, prompting cooks to turn to plant-based options instead. In Mediterranean regions, where olive trees thrived, olive oil became the go-to substitute, enabling the preparation of flavorful meals while adhering to religious guidelines.

This shift was both practical and spiritual. Substituting animal fats with olive oil aligned with the principles of restraint but still allowed food to remain enjoyable. Historical cookbooks often recommended olive oil for frying fish or stewing legumes. Over time, these practices shaped a dual culinary calendar: feast days featured rich dishes like meat stews cooked in pork fat, while fast days focused on oil-based meals such as fish, chickpeas, lentils, and seasonal vegetables.

Monasteries and Olive Oil Production

The increased reliance on olive oil for fasting meals also transformed monasteries into key producers. Many religious communities managed olive groves and presses, overseeing every stage of production - from pruning and harvesting to oil extraction and storage. Between the 11th and 15th centuries, Italian monasteries in regions under Venetian and Genoese influence operated large-scale olive oil production facilities. These operations not only met their own needs but also supplied oil for trade along Mediterranean routes and into northern Europe.

Monasteries used olive oil in various aspects of daily life. Beyond its role in sacraments, it was essential for cooking communal meals, treating wounds, and even maintaining tools. With surplus oil often sold or bartered, monasteries became both spiritual centers and economic powerhouses, contributing significantly to the monastic economy.

Common Christian Dishes Using Olive Oil

The production and availability of olive oil heavily influenced the creation of fasting dishes in medieval Christian kitchens. Meals for fasting days often included fried or stewed fish and hearty legume-based stews made with olive oil. Lentils, chickpeas, and broad beans were simmered with onions and garlic, providing meatless yet nourishing options for families during extended fasting periods.

Vegetables like cabbage, chard, eggplant, onions, and leeks were also staples, frequently sautéed or stewed in olive oil. These dishes were sometimes thickened with bread or grains to make them more filling. In southern Europe - regions like Italy, Spain, and southern France - where olives were plentiful, olive oil was a practical and affordable ingredient that made fasting meals both satisfying and flavorful. In contrast, northern Christian areas, where olives didn’t grow, relied on imported oil, which was costly and often reserved for religious ceremonies. This difference helped shape a distinctly Mediterranean Christian food culture, with olive oil at its heart.

Islamic Dietary Laws and Olive Oil

Halal Requirements and Olive Oil

In medieval Muslim households, olive oil became a staple, much like its role in Christian kitchens, largely due to its compatibility with Islamic dietary laws. Since these laws prohibit pork and its by-products, animal fats like lard were off-limits. Olive oil, being entirely plant-based, required no ritual slaughter and avoided any risk of forbidden contaminants. The Qur'an even refers to the olive as a "blessed tree", giving its oil the status of tayyib - a term that signifies pure and wholesome food. Islamic legal scholars ruled that olive oil remained halal as long as it wasn’t mixed with impure substances like pork fat or wine. This made it a trusted commodity, even when sourced from non-Muslim producers.

Medical and Cooking Uses in Islamic Culture

Islamic physicians held olive oil in high regard for its balanced and moistening qualities, which they believed supported digestion, improved skin health, soothed joints, and aided wound healing. This dual-purpose use ensured its place in both the kitchen and the medicine chest. In everyday cooking, olive oil became the go-to fat for frying vegetables, legumes, and fish. It was also used to moisten grains, prepare doughs, and enrich sweets. Market cooks and street vendors in Mediterranean Islamic cities relied on olive oil to create dishes that adhered to halal standards. During festive occasions like Ramadan iftar meals and Eid celebrations, premium olive oil was often used to elevate breads, pastries, and desserts.

Religious Meaning of the Olive Tree

The olive tree holds a special place in Islamic tradition, with the Qur'an - particularly in Surat an-Nur - drawing a comparison between its oil and divine light. This spiritual connection is further emphasized in Hadith literature, where the Prophet Muhammad advised, "Eat olive oil and anoint yourselves with it, for it is from a blessed tree". Such endorsements strengthened olive oil’s association with piety, health, and daily life in Muslim households. This reverence also motivated rulers, landowners, and charitable institutions to protect olive groves, ensuring a steady supply for uses ranging from cooking to lighting. In doing so, they underscored the olive tree’s importance not just as a resource but as a symbol of social and spiritual value.

Jewish Dietary Laws and Olive Oil

Kashrut Rules and Olive Oil's Neutral Status

In medieval Jewish dietary laws, olive oil held a special place as it was classified as pareve. This meant it was neither meat nor dairy, thanks to its plant-based origin. This classification gave cooks a lot of freedom since the same olive oil could be used in both meat and dairy dishes without breaking kashrut rules. However, once olive oil was cooked with either meat or dairy, rabbinic authorities required that any leftover oil or even the cookware used be treated as having absorbed that status. Proper koshering was necessary to reuse such items. To address this, households often kept separate cookware for meat and dairy while relying on a single, high-quality olive oil supply.

Communities also paid close attention to how olive oil was produced. If presses or storage jars had previously been used for non-kosher substances, the kosher status of the oil could be compromised. Jewish merchants took an active role in ensuring production methods adhered to kosher standards. Interestingly, rabbinic rulings sometimes advised purchasing olive oil from Muslim producers rather than certain Christian sources, as church use of these products often introduced complex commercial and ritual concerns.

Sabbath and Holiday Cooking

Olive oil wasn’t just a dietary staple - it was a cornerstone of ritual and family cooking. It played a key role in dishes like long-simmered Sabbath stews such as ḥamin and adafina. Since Jewish law prohibits cooking from Friday evening to Saturday night, families would prepare these dishes on Friday and let them simmer over a low flame throughout the Sabbath. Olive oil was essential in these recipes, preventing ingredients from sticking and enhancing the flavors of grains, legumes, and meats. Its pareve status made it especially convenient, as the same household stock could be used even when the dish, once cooked, was classified as meat. This practicality extended to holiday meals, ensuring adherence to dietary laws while allowing for advance preparation.

Jewish Identity and Olive Oil in Medieval Spain

Olive oil wasn’t just a cooking ingredient - it was a marker of Jewish identity in late medieval Spain. While Christians commonly used pork fat and Muslims leaned toward clarified butter, Jews were known for their use of olive oil in frying and stewing. The aroma of onions, garlic, and spices sautéed in olive oil became a defining feature of Jewish kitchens in cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Seville.

However, during the Spanish Inquisition, this culinary distinction became dangerous. Authorities often viewed the continued use of olive oil in traditional recipes as a sign of "secret Judaism" among conversos - Jews who had converted to Christianity, often under duress. To avoid suspicion, many conversos altered their recipes, adding pork to dishes like the Sabbath stew adafina. This adaptation eventually contributed to the development of the Spanish dish cocido. Despite these changes, the tradition of slow-cooked, olive-oil-rich stews remained a powerful, albeit risky, symbol of Jewish heritage.

sbb-itb-4066b8e

New Cooking Methods from Religious Restrictions

Frying Techniques with Olive Oil

In medieval kitchens, olive oil became a frying staple, largely influenced by dietary laws that spanned multiple faiths. These shared restrictions helped refine frying techniques across the region. Cooks would shallow-fry fish in a thin layer of olive oil, often coating it in flour or breadcrumbs to achieve a crisp, golden crust. Vegetables like eggplant, onions, and leeks were sautéed or pan-fried until tender and lightly browned, then incorporated into stews or egg-based dishes. For dough-based foods, such as early fritters, stuffed pastries, and celebratory breads, deep frying in larger amounts of oil was common. The dough would puff up beautifully during frying and was sometimes finished with a drizzle of honey or a sprinkle of spices, depending on the occasion.

By the 15th century, Jewish communities in cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Seville were renowned for their olive oil frying methods, especially for preparing Sabbath meals. They fried meats and crafted empanadas, infusing the air with the tempting aroma of garlic, onions, and spices sizzling in oil. Chronicler Andrés Bernáldez even noted how distinct this scent was in Jewish neighborhoods. However, during the Spanish Inquisition, this culinary hallmark became perilous, as authorities used it to accuse conversos of secretly maintaining Jewish traditions.

These refined frying methods eventually led to creative uses of olive oil in dressings and slow-cooked dishes.

Oil-Based Dressings and Slow-Cooked Dishes

Olive oil wasn’t just for frying - it became central to dressings and slow-cooked meals, especially those designed to accommodate religious observances. For instance, the sofrito - a base of onions and garlic lightly sautéed in olive oil - originated in Jewish Spanish kitchens and later became a cornerstone of Spanish cuisine. Jewish Sabbath restrictions on cooking inspired dishes like adafina, a slow-cooked blend of meat, chickpeas, grains, and vegetables. Prepared on Friday and left to simmer overnight, it was ready to be enjoyed warm on the Sabbath without requiring additional cooking.

Christian and Muslim households also embraced similar slow-cooking methods. Christian cooks prepared hearty bean and vegetable stews, enriched with olive oil, for feast-day eves and vigils, allowing the meal to cook with minimal attention before religious services. In Islamic homes, olive oil was essential for legume and vegetable dishes prepared ahead of Ramadan evenings, ensuring food was ready for the communal breaking of the fast. Olive oil’s ability to hold its flavor during long cooking times made it indispensable for these time-sensitive dishes.

These shared approaches to cooking fostered a broader exchange of culinary ideas among different faiths.

Recipe Sharing in Multi-Faith Regions

Olive oil’s versatility created a foundation for cross-cultural culinary exchanges in regions where multiple faiths coexisted. In medieval Spain and other diverse areas, daily interactions in markets, mills, and neighborhoods exposed cooks to a variety of techniques. Olive oil often served as the unifying ingredient. For example, Jewish frying methods, such as those used for stuffed pastries, influenced broader Iberian cuisine, introducing techniques that blended garlic, onion, and olive oil into everyday dishes.

While each faith adapted recipes to align with its own dietary laws, the core techniques remained consistent. Early versions of stuffed and fried doughs - prototypes of what would later become empanadas - originated in Jewish Sabbath cooking and were eventually incorporated into Christian Spanish cuisine, adjusted to fit different religious customs. Across Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions, shared practices like frying fish, sautéing eggplant, and simmering legume stews helped create a recognizable Mediterranean culinary style that transcended religious boundaries.

Medieval Olive Oil Practices Today

Quality and Freshness in Modern Olive Oil

Back in medieval times, freshly pressed olive oil was a prized treasure in monasteries and homes alike. It wasn’t just about taste - it was about preserving its natural flavor and health properties. Fast forward to today, and that same standard is alive and well. Producers like Big Horn Olive Oil stick to these time-honored practices, ensuring their Ultra Premium EVOO (Extra Virgin Olive Oil) is as fresh as it gets. They ship bottles within 1–3 months of harvest and select only the top 5% of olive harvests for their oils. This dedication ensures their EVOO is pure, never blended with other oils, and goes above and beyond standard EVOO requirements. Medieval cooks would approve.

"For the best tasting experience, we recommend consumption within 9 months of the olive oil crush date." - Big Horn Olive Oil

This focus on freshness doesn’t just enhance flavor - it also amplifies the health benefits.

Health Benefits and Cooking Uses

Centuries ago, people noticed olive oil’s healing properties. Today, science backs those observations. Ultra Premium EVOOs are packed with antioxidant biophenols and boast a high smoke point of 410°F or more. That makes them perfect for frying, sautéing, baking, or even drizzling over a salad. These versatile uses echo the way medieval cooks adapted olive oil to fit fasting rules and dietary needs across various faiths.

Big Horn Olive Oil: Carrying Forward a Historic Tradition

The legacy of high-quality olive oil endures, and Big Horn Olive Oil is keeping it alive. Their Ultra Premium EVOOs and Modena-sourced balsamic vinegars reflect the same care and precision medieval producers once practiced. By cold-pressing olives and delivering products shortly after harvest, they honor historical purity while meeting modern culinary expectations.

"My husband buys fine wine; I prefer the 'finest' olive oil!! We enjoy it daily." - Cleo H., verified buyer

This daily use of olive oil mirrors its importance in medieval kitchens, where it served as the go-to cooking fat. That tradition continues today, connecting past and present through every drop.

Why Was Olive Oil More Common Than Butter in Medieval Mediterranean Europe

Conclusion

The story of olive oil, from medieval kitchens to today's dining tables, highlights its role as a unifying ingredient across Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. In regions like medieval Spain, this versatile oil became a shared culinary cornerstone. Its distinct aroma, especially when used for frying, not only shaped Jewish identity but also left a lasting imprint on Spanish cooking traditions, such as sofrito.

Medieval dietary restrictions sparked a wave of culinary creativity. Techniques like frying, crafting oil-based dressings, and preparing slow-cooked dishes, such as the Jewish adafina, emerged out of necessity. These innovations formed the backbone of what we now recognize as Mediterranean cuisine.

Even today, olive oil retains its reputation for purity, adaptability, and healthful properties. Medieval monks valued freshly pressed oil for its rich flavor and medicinal qualities, a standard modern producers continue to uphold. Companies like Big Horn Olive Oil reflect this legacy, selecting only the finest 5% of olive harvests and ensuring freshness by shipping within 1–3 months of pressing. This dedication keeps the tradition alive, blending historical practices with contemporary excellence.

The olive tree, deeply rooted in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions, remains a symbol of nourishment and faith . The culinary foundations laid by medieval religious customs endure in the premium olive oils of today, preserving a connection between past and present through flavor, faith, and ingenuity.

FAQs

How did olive oil contribute to cultural connections between medieval religious communities?

Olive oil was more than just a kitchen staple in the medieval world - it acted as a bridge between religious communities. As a key ingredient in both daily meals and sacred rituals, it harmonized with various dietary laws, creating a shared thread across different faiths.

This mutual reliance on olive oil went beyond the plate. It spurred trade and fostered the exchange of ideas, helping to ease cultural and religious boundaries. Through shared culinary traditions and a collective respect for its role in spiritual practices, olive oil became a quiet yet powerful symbol of connection and cooperation.

How did monasteries contribute to the production and distribution of olive oil in medieval times?

Monasteries played a key role in the olive oil economy during the medieval period. They managed olive groves, operated presses to extract the oil, and established trade networks to distribute it far and wide.

Olive oil was indispensable, serving both sacred and practical purposes. It was a cornerstone of religious ceremonies and an essential ingredient in daily cooking, especially in areas where religious dietary rules shaped eating habits. By promoting its use, monasteries not only preserved its spiritual importance but also wove olive oil deeply into Mediterranean culinary traditions.

Why was olive oil widely used in medieval religious cooking?

Olive oil held a special place in medieval religious cooking, largely because it aligned with the dietary rules of many faiths. Its natural qualities made it suitable for sacred dishes, while its rich flavor and nourishing properties elevated traditional recipes. Beyond its taste and health appeal, olive oil's ability to meet religious dietary restrictions cemented its role as a staple in Mediterranean cuisine of the time.