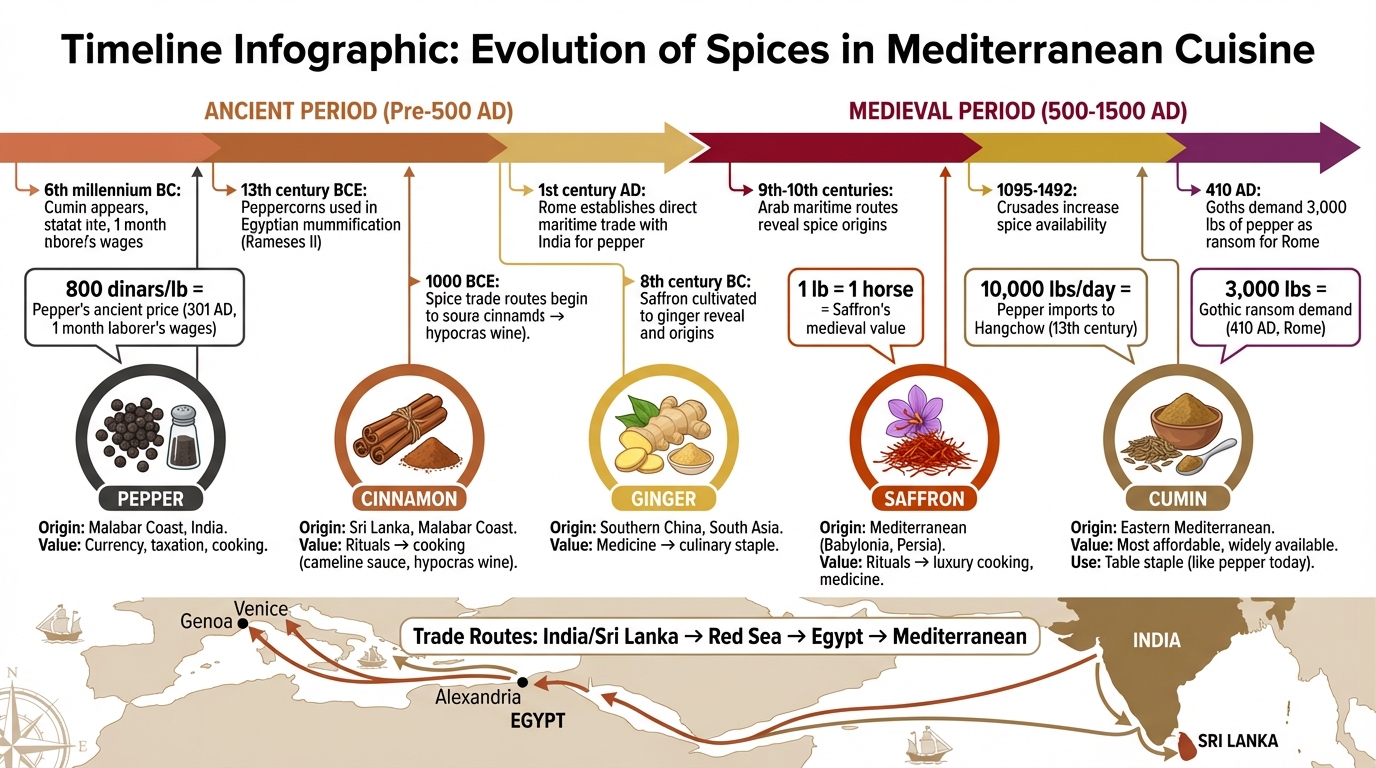

Evolution of Spices in Mediterranean Recipes

The Mediterranean cuisine we know today owes much of its flavor to the ancient and medieval spice trade. Here's a quick breakdown:

- Key Spices: Black pepper, cinnamon, ginger, saffron, and cumin were pivotal in transforming simple herb-based dishes into rich, aromatic meals.

- Origins: Spices like pepper and cinnamon came from India and Sri Lanka, while saffron and cumin were cultivated closer to the Mediterranean.

- Trade Routes: Starting around 1000 BCE, spices traveled thousands of miles through Egypt, Persia, and later, Italian maritime hubs like Venice and Genoa.

- Value: Spices were not just flavor enhancers - they symbolized wealth, served as currency, and had medicinal and preservative uses.

- Culinary Impact: By the medieval period, spices became staples in Mediterranean cooking, blending with local herbs to create complex, layered flavors.

The article dives into the history, sourcing, and uses of these spices, showing how they shaped Mediterranean cuisine and culture over centuries.

Evolution of Mediterranean Spices from Ancient to Medieval Times

1. Pepper

Ancient Sourcing and Uses

Black pepper, often called the "king of spices", originated on the Malabar Coast of India. From there, it traveled to the Mediterranean through intricate trade routes. Arab merchants played a key role, transporting pepper along the Incense Route from India and China to Greek markets. By the first century, Rome disrupted the Arab monopoly by establishing direct maritime trade with India via the Red Sea, making pepper more accessible.

Pepper's value in the ancient world extended far beyond the kitchen. Archaeologists discovered peppercorns in the nasal cavity of Rameses II, evidence of its use in mummification as early as the 13th century BCE. Hippocrates, the father of medicine, included pepper in his list of 400 herbal remedies, many of which are still relevant today. The Romans embraced pepper for its medicinal properties, incorporating it into treatments, lotions, perfumes, and even wines, recognizing its digestive and antibacterial benefits [6,7].

Medieval Sourcing and Uses

During the medieval era, pepper's importance grew, both economically and symbolically. From the 11th to the 15th centuries, the Red Sea and Egypt became key channels for importing pepper. Alexandria emerged as the central hub for redistributing the spice across the Mediterranean. Italian merchants, particularly Venetians, dominated this trade, marking a shift from earlier routes through the Persian Gulf (9th–11th centuries). This evolution elevated pepper from a simple seasoning to a prized commodity, even serving as a medium of exchange and taxation.

Pepper's value was so immense that it often acted as currency. It was used to pay taxes, tolls, and rent - a practice known as "peppercorn rent". In 1180, King Henry II of England established a pepperer's guild to oversee the cleaning and preparation of spices for sale, laying the groundwork for modern grocery practices. Emperor Diocletian's price edict in 301 AD underscored pepper's worth, setting its price at 800 dinars per pound, equivalent to a laborer's monthly wages. When the Goths besieged Rome in 410 AD, their ransom demands included 3,000 pounds of pepper, highlighting its status as a treasure.

Culinary Applications

In ancient times, black pepper was the only tropical spice regularly featured in cooking [10,14]. Roman recipes celebrated its sharp, pungent flavor. By the medieval period, Mediterranean cuisine leaned toward sweeter and more aromatic dishes, blending pepper with other exotic spices. Marco Polo observed its widespread use, noting that in the late 13th century, Hangchow imported a staggering 10,000 pounds of pepper daily. These culinary trends paved the way for modern uses, such as pairing black pepper with high-quality olive oils to enhance flavor.

sbb-itb-4066b8e

2. Cinnamon

Ancient Sourcing and Uses

Cinnamon traces its origins to Sri Lanka and the Malabar Coast of India. For centuries, Arab traders carefully guarded its source, keeping its value high by shrouding its origins in mystery until the 1st century AD. The spice also made its way to ancient Egypt through trade with Ethiopia, where it was prized not only as a flavoring agent but also for its medicinal properties. Archaeologists have even uncovered traces of cinnamon in Phoenician flasks from the early Iron Age, highlighting its long-standing significance.

In ancient times, cinnamon wasn’t a common ingredient in everyday cooking. Instead, it held a more specialized role in Roman and Greek traditions, where it was valued for its medicinal and ritual purposes. It was used in religious offerings, perfumes, and healing remedies, emphasizing its sacred status. This reserved role laid the groundwork for cinnamon's later prominence in medieval trade and cuisine.

Medieval Sourcing and Uses

During the medieval period, cinnamon transitioned from being a rare and exclusive commodity to a more widely available spice, thanks to evolving trade routes and cultural shifts. By the 9th and 10th centuries, its culinary applications had expanded significantly across Europe and the Mediterranean. Arab maritime trade routes, established during the 8th and 9th centuries, eventually revealed cinnamon's origins to Europeans. By the late 10th century, it had become one of the five essential spices in European trade. The Crusades (1095–1492) further boosted its availability, gradually making it more affordable.

Cinnamon’s role also evolved beyond its medicinal roots. It became a symbol of refinement and diplomatic importance. For example, in 1194, King Richard II of England gifted the King of Scotland four pounds of cinnamon along with two pounds of pepper as part of his daily allowance, showcasing its value as a prestigious offering. Similarly, in the 14th century, King Jean le Bon of France purchased "cinnamon flowers" (dried buds of Indonesian cassia) at a price five times higher than standard cinnamon bark. Medieval physicians also found new uses, heating cinnamon in wine to treat digestive problems and gum decay, believing it had antiseptic properties for the intestines. This elevated status helped integrate cinnamon into the culinary traditions of the time.

Culinary Applications

Cinnamon became a cornerstone of medieval cooking, finding its way into some of the most celebrated dishes of the era. The 14th-century cookbook Le Viandier de Taillevent included recipes for "cameline sauce", a popular accompaniment for meat dishes, with cinnamon as its defining ingredient. Another standout creation was hypocras, a spiced wine sweetened with honey and flavored with cinnamon and ginger. French cuisine, in particular, embraced the pairing of cinnamon and ginger, though in England, cinnamon was used in fewer than 10% of recipes during this period.

By around 1500 AD, cinnamon had become one of the more affordable spices in Europe, alongside pepper, ginger, sugar, and olive oils. Meanwhile, others like cloves and nutmeg remained significantly more expensive, costing roughly three times as much as cinnamon.

Cultural Significance

In medieval Mediterranean societies, cinnamon symbolized luxury and social status. According to Paul Freedman of Yale University, spices like cinnamon were prized for their ability to create a fragrant, opulent atmosphere. European demand for cinnamon and other spices during the late Middle Ages (1200–1500) was described as "insatiable". The spice was also considered "warming", which influenced its use in medicinal wines and digestive treatments. While its ancient uses were largely tied to rituals and healing, the medieval period elevated cinnamon into a culinary treasure, representing wealth and sophistication through elaborate, spice-laden feasts.

3. Ginger

Ancient Sourcing and Uses

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has its roots in Southern China and South Asia, eventually finding its way to the Mediterranean via the Indian Ocean trade network. Ancient traders moved ginger through key Red Sea ports, with Arab merchants carefully guarding the spice's origins to maintain their trade dominance.

Unlike black pepper, a common ingredient in Roman cuisine, ginger was primarily valued for its medicinal properties, use in perfumes, and its role in religious and funeral rituals. Ancient texts highlight its healing qualities, with Dioscorides' De Materia Medica serving as a trusted medicinal reference for over 1,500 years. While ginger occasionally appeared in early culinary texts like the Roman cookbook Apicius and the 6th-century Byzantine work Epistula Anthimi, its use in cooking was relatively rare during this time.

Medieval Sourcing and Uses

During the medieval period, ginger’s role expanded significantly, both in trade and application. By the 5th century AD, mariners carried fresh ginger to prevent scurvy on long voyages. Arab traders, who dominated maritime routes in the 8th and 9th centuries, gradually revealed more details about the spice’s origins to Europeans, though ginger remained a prized commodity.

In the early Middle Ages, ginger was so valuable that a pound of it could be traded for the equivalent of a sheep. The Portuguese discovery of sea routes to India in 1501 brought larger quantities of ginger to Mediterranean markets like Lisbon, increasing its availability. Marco Polo’s 13th-century accounts provided detailed descriptions of ginger cultivation along India’s Malabar Coast and in Peking (Kain-du), offering Europeans a clearer picture of its production.

Culinary Applications

This increased availability allowed ginger to take on a more prominent role in medieval cuisine. It became a key ingredient in high-end Mediterranean dishes, frequently featured in complex spice blends like atraf al-tib, which included ginger alongside lavender, betel, and nutmeg. Cooks also used it to mask the flavors of aging food and to enhance spiced wines.

Paul Freedman, a Yale history professor, noted:

The recipes of classical Greece and Rome favor sharp flavors, while those of the Middle Ages result in dishes that are sweeter and more perfumed.

Ginger’s inclusion in these evolving recipes reflects the broader shift in medieval tastes, moving away from the sharp flavors of antiquity toward more aromatic and layered culinary profiles, particularly favored by the nobility.

Cultural Significance

Ginger’s journey through the Mediterranean reflects its transformation from a simple seasoning to a symbol of sophistication and luxury. Its exotic Eastern origins added to its appeal among the medieval elite. Beyond its status as a luxury item, ginger’s medicinal uses - well-documented by early authorities - further elevated its importance. Medieval apothecaries, influenced by Arabian medical knowledge and teachings from the School of Salerno, incorporated ginger into elixirs and remedies for digestion. In Ayurvedic practices, ginger was often chewed with betel-nut leaves after meals to aid digestion. This dual role as both a symbol of wealth and a trusted remedy solidified ginger’s prominent place in Mediterranean culture.

4. Saffron

Ancient Sourcing and Uses

Saffron has been cherished for centuries, making its mark as one of the earliest cultivated Mediterranean spices. Back in the 8th century BC, King Merodach-Baladan II grew saffron in the royal gardens of Babylon, showcasing its importance even in ancient times. Later, Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (668–633 BC) cataloged saffron among aromatic plants, further emphasizing its value in Mesopotamian culture.

What sets saffron apart from many other spices is its local cultivation in regions like Babylonia and Persia, rather than being imported from far-off lands. By the 6th century BC, ancient Persians were already extracting essential oils from saffron. Even the biblical Song of Solomon, dating back to the 17th century BC, mentions saffron as a culinary spice, reflecting its early role in food preparation. However, in the ancient world, saffron was mostly reserved for religious offerings, burial rituals, and medicinal purposes rather than everyday cooking. Hippocrates (460–377 BC), often called the "Father of Medicine", included saffron in nearly 400 herbal remedies, many of which are still in use today. These early practices cemented saffron's reputation as a highly valued commodity, paving the way for its prominence in later eras.

Medieval Sourcing and Uses

By the Middle Ages, saffron had become one of the most prized and tightly controlled spices in Mediterranean trade. Its value was extraordinary - just one pound of saffron was worth as much as a horse. To protect its purity and prevent fraud, Nuremberg introduced the Safranschou code, which imposed severe penalties for adulterating saffron.

Arab physicians in the 9th century AD took saffron’s medicinal potential to new heights, creating syrups and flavoring extracts that expanded its therapeutic uses. These advancements influenced European apothecaries, who adopted Arabian medical knowledge and incorporated saffron into their own remedies during the Middle Ages. The strict regulation of saffron trade ensured its rarity and high cost, which in turn shaped its culinary and medicinal significance.

Culinary Applications

Saffron's role in cooking grew notably during the medieval period. It became a key ingredient for masking the flavors of aging foods and enhancing dishes like spiced wines and vinegars. This transformation played a part in the "sweet and sour revolution" that characterized Renaissance cuisine. These culinary innovations marked a turning point in Mediterranean cooking traditions.

Cultural Significance

Saffron’s dual identity as both a luxury ingredient and a medicinal powerhouse elevated its status as a symbol of wealth and power. It held a prominent place in royal courts and religious ceremonies, further solidifying its reputation as a spice of distinction.

5. Cumin

Ancient Sourcing and Uses

Cumin has a history that stretches back thousands of years. Archaeological finds show its presence in the Mediterranean as far back as the 6th millennium BC. Wild cumin seeds were discovered at the underwater site of Atlit-Yam, while cultivated seeds were unearthed in 2nd millennium BC Syrian excavations. It is believed that cumin originated in the Eastern Mediterranean, Southwestern Asia, or Central Asia. In ancient Egypt, cumin was highly valued - not just as a flavorful spice but also as a preservative in mummification processes.

By the 7th century BC, King Ashurbanipal of Assyria (668–633 BC) included cumin in his records of aromatic plants and herbal flavors, written in cuneiform script. In ancient Greece, cumin was so essential that it had a permanent place on dining tables, much like black pepper does today. On the island of Crete, during the Minoan civilization, cumin was stored in palace storerooms, as recorded on Linear A tablets.

The Romans took cumin's uses even further. They infused it into spiced wines, specialty flavors, scented balms, post-bath oils, and even healing plasters. Its significance is also noted in the New Testament, where Matthew 23:23 mentions it in the context of religious tithes: "a tenth of your spices - mint, dill, and cumin". These early uses laid the groundwork for cumin's later role in medieval cooking and culture.

Medieval Sourcing and Uses

During the medieval period, cumin continued to thrive as a locally grown and traded spice throughout the Middle East. Unlike exotic imports like cloves and nutmeg from Southeast Asia, cumin was readily available and cultivated closer to home. By the 9th century, Arab physicians had begun crafting syrups and extracts from cumin, which later influenced European medicinal practices. At the same time, medieval folklore ascribed mystical properties to the spice, adding to its allure.

Cultural Significance

Over time, cumin transitioned from its early ritualistic and medicinal roles to becoming a cornerstone of everyday cooking in the Mediterranean and surrounding regions. Its journey - from being used in mummification and religious offerings to becoming a staple in kitchens - reflects its deep-rooted cultural importance. Today, cumin is a key ingredient in Mediterranean and Arabic cuisines, forming the backbone of many spice blends and traditional dishes that define the region's culinary identity.

Spices: Ancient Trade Networks

Pros and Cons

Spices have always walked a fine line between luxury and necessity, shaped by changing trade routes and culinary preferences. Here's a closer look at how these spices balanced their economic and culinary roles through history.

Pepper was a staple in Roman kitchens, celebrated as the go-to tropical spice for its sharp, bold flavor. However, its steep price - around 800 dinars per pound - meant it was a luxury reserved for the wealthy. By the medieval era, pepper's value skyrocketed to the point where it was even used as a form of currency. This demand also gave rise to fraud, with dishonest merchants earning the moniker "dissembling pepperers".

Cinnamon and ginger faced their own hurdles. Cinnamon, with its mysterious origins and high shipping costs, was rarely used in everyday cooking . Ginger, initially valued for its medicinal properties, gradually found its way into culinary recipes. However, its price - equivalent to one sheep per pound - made it a costly addition to the kitchen. Both spices relied heavily on long maritime trade routes, adding to their exclusivity.

Saffron symbolized opulence. Despite being native to the Mediterranean, its labor-intensive harvesting process made it extraordinarily expensive - one pound could cost as much as a horse. Its high value also made it a frequent target for adulteration, often mixed with cheaper plants to increase profit margins.

Cumin, on the other hand, was the most accessible of these spices. Grown abundantly across the Mediterranean, it was affordable and widely used. However, its very ubiquity made it less desirable compared to the rarer, more exotic spices.

The table below highlights the benefits and challenges of these spices across ancient and medieval times.

| Spice | Period | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pepper | Ancient | Dominant tropical spice in Roman cuisine; loved for its sharp flavor | Extremely expensive, affordable only for the elite |

| Medieval | Widely traded and highly valued | Susceptible to commercial fraud | |

| Cinnamon | Ancient | Used in sacred oils and rituals | Rarely used in daily cooking due to secretive origins |

| Medieval | Added a desirable aroma to dishes | High costs tied to maritime trade | |

| Ginger | Ancient | Known for medicinal and digestive benefits | Hard to transport fresh, mostly available dried |

| Medieval | Essential in sauces and gingerbread | Expensive and quality varied | |

| Saffron | Ancient | Used as a dye and for its distinct aroma in rituals | Labor-intensive harvesting made it extremely costly |

| Medieval | Provided vibrant color and symbolized luxury | Cost equivalent to a horse; vulnerable to adulteration | |

| Cumin | Ancient | Affordable and widely available seasoning in the Mediterranean | Considered less exotic compared to imported spices |

| Medieval | Reliable and inexpensive | Lacked the allure of rarer, imported spices |

Pairing Spices with Premium Olive Oils Today

The art of combining spices with premium olive oils, rooted in medieval culinary traditions, continues to thrive in modern kitchens. This age-old practice, which brought together quality fats and flavorful spices, remains a cornerstone of Mediterranean cooking. Today, home chefs can elevate their meals with premium extra virgin olive oils (EVOOs) that not only enhance taste but also offer numerous health benefits.

Take saffron, for instance. Known for its pungent yet sweet flavor, saffron pairs beautifully with the herbaceous notes of robust Italian EVOOs like Big Horn Olive Oil's Coratina. Drizzle saffron-infused olive oil over dishes like paella or bouillabaisse to amplify the spice's vivid color and aromatic qualities[22,23].

Other spices, such as cumin and cinnamon, also shine when combined with high-quality olive oils. Toasting cumin seeds before grinding them releases a warm, earthy flavor that blends seamlessly with the peppery kick of premium EVOOs. This pairing works wonderfully in tomato-based sauces, hearty stews, and even salad dressings. Cinnamon, with its warm and slightly bitter undertones, complements EVOO beautifully, enriching dishes with its spicy depth while contributing to a diet rich in antioxidants, monounsaturated fats, and polyphenols.

To maximize both flavor and health benefits, choose cold-pressed oils. These are extracted at temperatures below 80.6°F, preserving essential nutrients that enhance the synergy between spices and oils. This method echoes ancient techniques, ensuring the natural potency of ingredients remains intact. For example, Big Horn Olive Oil cold-presses its products within two hours of harvest, maintaining their superior quality. The growing appreciation for such pairings is reflected in the olive oil market, which was valued at $13.77 billion in 2019 and is projected to grow at a 6.3% annual rate through 2027.

Spices, condiments and extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) are... precious allies for our wellbeing... they have antioxidant, antiviral, antibiotic, anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory properties.

- Irene Dini and Sonia Laneri, Department of Pharmacy, University of Naples Federico II

Conclusion

Spices have journeyed from their origins as sacred and medicinal substances to becoming staples in kitchens worldwide, thanks to evolving trade routes and cultural exchanges. During the Roman era, tropical spices began to make their way into kitchens, though black pepper was the standout ingredient regularly used in cooking at the time. These early developments hinted at the sweeping changes that would later define the medieval spice trade.

The rise of maritime trade through the Red Sea and Persian Gulf replaced the secretive land-based caravans, dismantling Arab monopolies and establishing Italian cities like Venice and Genoa as major spice distribution hubs by the 12th century. This shift made spices more accessible, transforming them from rare luxuries into culinary staples. Black pepper, for instance, became so valuable during shortages that it was even used as currency. These changes not only redefined medieval cooking but also laid the groundwork for the culinary traditions we enjoy today.

Cultural interactions during the Crusades and advancements by Islamic scientists introduced new methods for extracting essential oils, altering Mediterranean flavoring techniques. Ancient Greek and Roman recipes often leaned toward sharp, bold flavors, but medieval cooks embraced sweeter, more fragrant blends with spices like cinnamon, saffron, and cloves. This transition marked an early wave of culinary globalization, connecting South Asia, North Africa, and Europe - a network of influence that remains evident in modern cuisine.

Mediterranean cooking today still carries the imprint of these medieval innovations. From the careful pairing of premium olive oils with exotic spices to the balance of local herbs and imported flavors, the use of spices continues to serve both culinary and health purposes. What once symbolized luxury and wealth has evolved into a cornerstone of a health-conscious, globally inspired culinary tradition. Each drizzle of extra virgin olive oil paired with a touch of spice reflects a legacy that began centuries ago.

FAQs

How did spices shape the economy and culture of the Mediterranean region?

Spices have long been a driving force behind the Mediterranean’s economy and cultural identity, shaping its history from ancient times through the Middle Ages. Luxuries like pepper, cinnamon, and saffron were in high demand, traveling along extensive trade routes from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Peninsula to bustling Mediterranean ports like Alexandria and Venice. These goods were so valuable that, by weight, they often surpassed the price of gold. Their trade not only created wealthy merchant classes but also financed naval expeditions and led to innovations in banking and credit systems to handle the complexities of long-distance commerce. The allure of spices even pushed European explorers to find sea routes to the East, setting the stage for the colonization of distant lands.

Beyond economics, spices carried deep cultural meaning, symbolizing wealth, hospitality, and even spiritual importance. In ancient Greek and Roman kitchens, they elevated simple dishes, while in medieval times, they were often paired with sweet sauces to create extravagant meals fit for the elite. Spices were also prized for their medicinal qualities and played roles in religious ceremonies, weaving a shared culinary and cultural thread throughout the Mediterranean. Today, companies like Big Horn Olive Oil pay homage to this rich history by crafting infused extra-virgin olive oils that blend traditional Mediterranean herbs with historic spice combinations, offering a modern take on this timeless legacy.

Why were spices like saffron and pepper used as currency during medieval times?

Spices like saffron and pepper were considered treasures in medieval times, prized not just for their flavor but for their rarity and value. Their demand spanned vast regions, making them a dependable and portable form of wealth. In fact, these spices were often as valuable as gold by weight, which made them a favored trade currency among merchants.

Their appeal wasn’t just practical - spices carried an air of prestige due to their exotic origins and scarcity. This combination of utility and luxury firmly established them as both a symbol of affluence and a practical substitute for traditional money.

How have the uses of spices changed from ancient Mediterranean times to today?

In ancient Mediterranean societies, spices were far more than simple flavoring agents - they were symbols of wealth, power, and even spiritual significance. These prized ingredients made their way into elite feasts, sacred rituals, and practical uses like preserving food or masking unpleasant tastes. Spices like black pepper and cinnamon were so highly valued that they journeyed across vast trade routes, connecting distant cultures and economies.

Fast forward to today, and spices remain an essential part of cooking, though their role has evolved. Now, they’re celebrated for enhancing global cuisines and offering health benefits. Modern recipes combine the sharpness of pepper, the warming depth of cinnamon, or the fiery kick of chili with fresh ingredients like herbs and citrus, creating layers of flavor. Beyond taste, spices are prized for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, aligning perfectly with popular culinary movements like fusion cuisine and farm-to-table dining.